1988 Massacre

1988 Massacre of Political Prisoners in Iran

A Crime Against Humanity

The facts

- In 1988, the government of Iran massacred 30,000 political prisoners.

- The executions took place based on a fatwa by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini.

- Three-member commissions known as ‘Death Commissions’ were formed across Iran sending political prisoners who refused to abandon their beliefs to execution.

- The victims were buried in secret mass graves.

- The perpetrators continue to enjoy impunity.

- Since 2016, the names of nearly 100 ‘Death Commission’ members have been revealed. Many still hold senior positions in the Iranian judiciary or government. They include the current Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi.

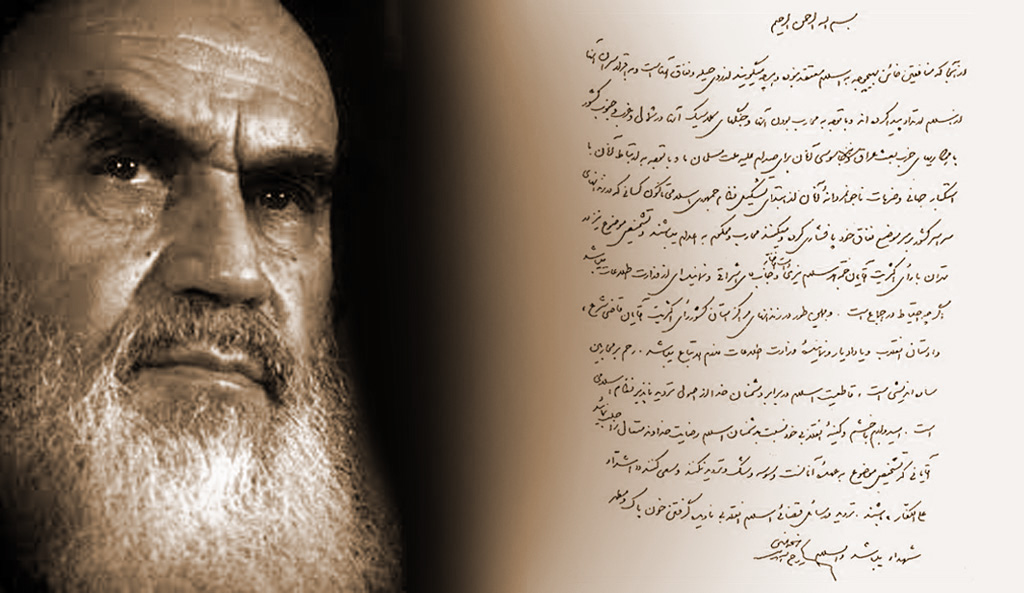

Khomeini’s Fatwa

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa in July 1988 ordering the execution of imprisoned opponents, including those who had already been tried and were serving their prison terms. This was the beginning of what turned out to be the biggest massacre of political prisoners since World War II.

Following the decree, some 30,000 political prisoners were extra-judicially executed within several months.

Khomeini’s decree called for the execution of all political prisoners affiliated to the main opposition group People’s Mojahedin Organisation of Iran (PMOI or MEK) who remained loyal to the organisation.

The decree reads: “As the treacherous Monafeqin [PMOI] do not believe in Islam and what they say is out of deception and hypocrisy, and as their leaders have confessed that they have become renegades, and as they are waging war on God, and…. It is decreed that those who are in prison throughout the country and remain steadfast in their support for the Monafeqin [PMOI] are waging war on God and are condemned to execution.”

The decree was so ruthless even by the standards of the Islamic Republic of Iran, that the Chief Justice sought clarification with the following questions:

- Does the decree apply to those who have been in prison, who have already been tried and sentenced to death, but have not changed their stance and the verdict has not yet been carried out, or are those who have not yet been tried also condemned to death?

- Those Monafeqin [PMOI] prisoners who have received limited jail terms, and who have already served part of their terms, but continue to hold fast to their stance in support of the Monafeqin [PMOI], are they also condemned to death?

- In reviewing the status of the Monafeqin [PMOI] prisoners, is it necessary to refer the cases of Monafeqin [PMOI] prisoners in counties that have an independent judicial organ to the provincial centre, or can the county’s judicial authorities act autonomously?

Khomeini’s response was even more ruthless: “In all the above cases, if the person at any stage or at any time maintains his [or her] support for the Monafeqin [PMOI], the sentence is execution. Annihilate the enemies of Islam immediately. As regards the cases, use whichever criterion that speeds up the implementation of the verdict.”

Death Commissions

In his decree, Khomeini, ordered the formation of three-member panels, known as “Death Commissions” throughout the country to implement his order of executing all political prisoners remaining loyal to their belief and political affiliation. It was not limited to Tehran or provincial capitals; every county with a judicial system implemented the decree. Thus, a systematic murder machine began operating all over the country with unprecedented speed. It took only a few minutes for the Death Commissions to determine each case brought before them.

Each panel included a religious judge, prosecutor and a representative from the Ministry of Intelligence. They were named by the prisoners and human rights organization as “Death Commissions.”

The procedures were very simple. They would call the prisoners one by one and ask them if they still supported the PMOI; if the answer was yes, they would be executed. Even if the prisoners avoided expressing support for the PMOI, they had to pass other tests such as agreeing to make a ‘confession’ on television against the PMOI? Then they would be asked if they would cooperate with the regime against other prisoners who remained loyal to the PMOI? A negative response in any of these cases could automatically lead to the prisoner receiving an execution sentence. Some weeks after the start of the massacre of PMOI affiliates, political prisoners affiliated with other groups who refused to cooperate with the regime were also executed.

Most of the victims were political prisoners serving their sentences; many had completed their sentences but were kept in prison and there were no new charges or even allegation against them. Others, who had previously been jailed and later freed, were rearrested without charge and summarily executed over their continued support for the PMOI.

The corpses were not handed over to their families. Indeed, many families did not know what had happened to their loved ones. The regime feared protests when families were eventually informed about the death of their loved ones. Therefore, in order to prevent such protests, the regime laid conditions for informing families of the burial site of their loved ones. Among the conditions were that the family must not hold a ceremony or put up their loved ones photos in their home; nor must they hold any sort of public protest. In the end, however, the families were never informed of their loved ones’ place of burial. The executed prisoners were buried in various unknown mass graves. Some of the mass graves have been discovered over the years.

The emerging evidence

Hossein-Ali Montazeri was Khomeini’s designated successor at the time of the massacre in 1988. However, he wrote a series of letters to Khomeini opposing the executions. He told Khomeini that the PMOI was “an idea” and “a logic” which would be strengthened by these killings. “If you insist on your decree … spare the women with children.” Khomeini not only ignored his recommendations, but became extremely enraged and ousted Montazeri, who subsequently was put under house arrest until his death in 2009.

On 9 August 2016, twenty-eight years after the carnage, an audio recording of Montazeri’s meeting on 15 August 1988 with top officials responsible for the massacre was published online by his son Ahmad Montazeri. In the audio file Montazeri could be heard addressing the “Death Commission” of Tehran consisting of four people: Mostafa Pourmohammadi, representative of the Ministry of Intelligence (MOIS) in the Commission; Hossein Ali Nayyeri, the sharia judge; Morteza Eshraghi, the public prosecutor; and Ebrahim Raisi, the deputy prosecutor, who collectively decided on the executions in the Iranian capital. (Raisi is currently Iran’s Judiciary Chief and will soon become Iran’s President.)

Montazeri told the Death Commission: “The greatest crime in the Islamic Republic, for which history will condemn us, has been committed by you.”

Iranian civil society demands justice

Since the summer of 2016, Iranian civil society has defied the government by breaking the taboo on openly discussing the massacre and demanding justice. In a report published on 2 August 2017, Amnesty International pointed to a campaign by Iran’s younger generation who seek an inquiry into the mass killings of political prisoners in 1988.

The report said: “Human rights defenders targeted for seeking truth and justice include younger human rights defenders born after the 1979 Revolution who have taken to social media and other platforms to discuss the past atrocities, and attended memorial gatherings held at Khavaran.“

It adds that there has been “a chain of unprecedented reactions from high-level officials, leading them to admit for the first time that the mass killings of 1988 were planned at the highest levels of government.“

A video clip of a speech on 22 April 2017 by a student at Tabriz University challenging a top former Revolutionary Guards commander and condemning the 1988 massacre in Iran was widely circulated on social media: “Your theory and your discussions defend the horrific, inhumane, illegal and irreligious massacres of 1988. … We will neither forgive, nor forget your betrayals and crimes. Our people will avenge the pain and grief of the mothers [of the martyrs] of our nation.”

Dr. Mohammad Maleki, the first chancellor of Tehran University after the 1979 revolution and a prominent dissident in Iran, who spent many years in prison under torture, pointed out in an interview with Dorr TV on 14 August 2016 that more than 30,400 of the executed prisoners were members of the opposition People’s Mojahedin (PMOI or MEK) and 2000-3000 were leftists.

Mohammad Nourizad, a close associate to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei prior to the 2009 uprising in Tehran, wrote: “Here, in a matter of 2 or 3 months, 33,000 men, women, young and old were imprisoned, tortured and executed. Their bodies were taken to Khavaran Cemetery and barren lands by trucks and buried in mass graves, happy of what they had done…”

Reza Malek, a former intelligence officer, revealed that according to documents he had personally seen, 33,700 prisoners were executed in 1988.

The Iranian people used the campaign period prior to the undemocratic ‘election’ to highlight the call for justice.

In Qom in May 2017, Iranians chanted against Presidential candidate Raisi: “He is the murderer of 1988“.

Iranian political prisoner Maryam Akbari-Monfared on 15 October 2016 made an official complaint from inside prison to the Iranian judiciary over the execution of her siblings in the 1988 massacre. According to Amnesty International she was subsequently put under further pressure in prison.

In a report (A/HRC/34/65) to the Human Rights Council on 17 March 2017, the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Iran criticized the Iranian authorities for repressing victims’ families.

The public attention to this subject has forced the government to engage in massive propaganda to defend the massacre by misrepresenting the facts and blaming the victims.

Iranian officials act with impunity

Ayatollah Ahmad Khatami, a board member of Iran’s Assembly of Experts and Tehran’s acting Friday prayer leader, in a sermon on 21 July 2017 cried out against the calls for justice.

Khatami said: “Confronting them (imprisoned dissidents) and wiping out the Monafeqin (PMOI) was one of the Imam’s most righteous and valuable actions, and all of the persons who complied with his edict should be awarded a Medal of Honour. … However, those who on their websites have switched the place of martyrs and murderers should repent and beg for forgiveness.”

His remarks echoed those of Supreme Leader Khamenei who said on 4 June 2017 that the 1980s were an era of great glory, stressing that “the place of the victim and the executioner should not be changed.”

Mostafa Pour-Mohammadi who was Iran’s Justice Minister until August 2017 was quoted on 28 August 2016, by the state-run Tasnim news agency as saying: “God commanded show no mercy to the nonbelievers because they will not show mercy to you either and there should be no mercy to the [PMOI] because if they could they would spill your blood, which they did. … We are proud to have carried out God’s commandment with regard to the [Mojahedin] and to have stood with strength and fought against the enemies of God and the people.“

In an interview with the state-affiliated Tarikh Online website, aired on 9 July 2017, Ali Fallahian, Iran’s former Intelligence Minister, acknowledged that Khomeini’s 1988 fatwa called for the eradication of all affiliates of the PMOI. Fallahian said that even PMOI supporters whose only crime was to distribute the group’s literature or buy bread or other provisions for them were found guilty of waging war on God and executed.

Fallahian has three international warrants for his arrest; two by German and Swiss magistrates over his role in the assassination of Iranian dissidents abroad, and an Interpol Red Notice over his role in the terrorist bombing of a Jewish community centre in Buenos Aires in 1994.

Mohsen Rafiqdoost, Iran’s former Minister for the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC), in an interview with the state-run Mehr News Agency on 18 July 2017 defended the 1988 massacre, adding: “Today too if we find [PMOI members], we will do the same with them.”

Ebrahim Raisi’s campaign in the weeks leading to the May 2017 election continuously sent out messages via the social network Telegram defending the 1988 massacre through misrepresentation of the facts.

With Raisi standing by his side, Yasser Mousavi, the Friday prayers’ leader in Varamin, said at a Raisi campaign rally on 12 May 2017: “This grand figure who is standing next to me is proud to have executed the members of the PMOI.”

After being declared the winner of Iran’s Presidential election of June 2021, Raisi used his first press conference on 21 June 2021 to defend his role in the 1988 massacre.

Articles seeking to justify the massacre have been published across state media, including online publications, and Intelligence Ministry outlets.

Since 2016, the 1988 massacre has gradually turned into a growing demand by the victims’ families and the Iranian people for transparency and prosecution of those involved. This has already been a major development both from a human rights perspective and from a purely political perspective, indicating that even after 32 years, the massacre remains a benchmark for the Iranian people to judge different factions of the ruling system. Many describe the issue of the massacre as the collective conscience of the Iranian people, which cannot be set aside until the perpetrators are brought to justice.

Special Rapporteur’s findings

In 2017, the previous UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Iran, Asma Jahangir, informed the General Assembly [1] :

“Between July and August 1988, thousands of political prisoners, men, women and teen-agers, were reportedly executed pursuant to a fatwa issued by the then Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khomeini. A three-man commission was reportedly created with a view to determining who should be executed.”

“Over the years, a high number of reports have been issued about the 1988 massacres. If the number of persons who disappeared and were executed can be disputed, overwhelming evidence shows that thousands of persons were summarily killed. Recently, these killings have been acknowledged by some at the highest levels of the State. The families of the victims have a right to know the truth about these events and the fate of their loved ones without risking reprisal. They have the right to a remedy, which includes the right to an effective investigation of the facts and public disclosure of the truth; and the right to reparation.”

On 26 February 2018, Secretary-General António Guterres told the Human Rights Council [2] :

“OHCHR continued to receive letters from families of the victims who were summarily executed or forcibly disappeared during the events of 1988. … The Secretary-General remains concerned by the difficulty the families faced in obtaining information about the 1988 events and the harassment of those continuing to advocate for further information related to these events.”

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, told NGOs on 9 March 2018:

“The 88 massacre, the allegations of the massacres in 88, the summary executions and enforced disappearances of thousands of political prisoners – men, women and children – we have received a great deal of information from you. … And the recommendations have been made to the national authorities to investigate independently and impartially of course given all the attention given to this by the victims’ families.”

An ongoing Massacre

The fatwa issued by Iran’s Supreme Leader has never been rescinded. On 25 July 2019, in an interview [3] with the state-run Mosalas magazine, Mostafa Pour-Mohammadi, Advisor to the Judiciary Chief and a former member of the Death Commissions, defended the 1988 massacre and said newly-caught PMOI activists would face the capital punishment.

UN human rights experts decry “crime against humanity”

On 3 September 2020, seven United Nations Special Rapporteurs wrote to the Iranian authorities stating that the 1988 extrajudicial executions and forced disappearances of thousands of political prisoners “may amount to crimes against humanity.”

The letter states that the families of the victims, survivors and human rights defenders are today the “subject of persistent threats, harassment, intimidation and attacks because of their attempts to seek information on the fate and whereabouts of the individuals and their demands for justice.”

The UN human rights experts also expressed alarm at the destruction of mass graves and lack of investigation and prosecution of the perpetrators.

“There is a systemic impunity enjoyed by those who ordered and carried out the extrajudicial executions”, they said, adding: “Many of the officials involved continue to hold positions of power including in key judicial, prosecutorial and government bodies.” They include the current Judiciary Chief and Justice Minister.

The UN experts stated that the failure of UN bodies to act over the 1988 massacre has “had a devastating impact on the survivors and families” and “emboldened” the Iranian authorities to “conceal the fate of the victims and to maintain a strategy of deflection and denial.”

The UN experts suggested that the international community should “investigate the cases including through the establishment of an international investigation.”

Time for international action

Crimes against humanity are not bound by the statute of limitations, and even though the 1988 massacre was perpetrated 32 years ago, it is still prosecutable today. Iranian officials brazenly claim Khomeini’s fatwa still stands against the PMOI dissidents. The perpetrators of the 1988 massacre today run the Iranian government and Judiciary. The survivors are still alive, and the evidence is all readily available.

Until the international community holds the perpetrators of the 1988 massacre to account, Iran’s authorities would continue to be emboldened to further crack down with impunity on present-day protesters. Iranian officials construe silence and inaction by the international community as a green light to continue and step up their crimes.

On 3 May 2021, more than 150 former United Nations officials and renowned international human rights and legal experts joined JVMI in writing to UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet, calling for an international Commission of Inquiry into the 1988 massacre of thousands of political prisoners in Iran.

Signatories to the open letter include former UN High Commissioner and Irish President Mary Robinson, a former UN Deputy Secretary-General, 28 former UN Special Rapporteurs on human rights, and the chairs of previous UN Commissions of Inquiry into human rights abuses in Eritrea and North Korea.

Distinguished legal professionals signing the appeal include the former Chief Prosecutor of the UN International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, a former Special Prosecutor at the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, and the first President of the UN Special Court for Sierra Leone.

The UN Human Rights Council must urgently set up a commission of inquiry into the 1988 massacre and achieve justice for the victims of that crime against humanity.

UN High Commissioner Michelle Bachelet should support the launch of independent fact-finding missions into the 1988 massacre.

—

[1] https://undocs.org/A/72/322

[2] https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session37/Documents/A_HRC_37_24.docx