Mostafa Naderi, a former Iranian political prisoner on the 1988 massacre he narrowly escaped

When I heard Canadian-Iranian professor Homa Hoodfar was released from the notorious Evin prison and left Iran safely after months of incarceration, I was relieved, as I have a sense of what she went through.

In 1981, my political dissent and human rights activities landed me in Iranian prison for 11 years — six of them in northern Tehran and 5½ in solitary confinement. My imprisonment took place at a crucial time, and if not for a handful of chance occurrences, I would have surely been one of the 30,000 victims of Iran’s 1988 massacre of political prisoners.

I was 17 when I was arrested for supporting the opposition People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI/MEK) and selling its publication. Seven years later, I was still being tortured and, after I lost consciousness while being bloodily flogged on the soles of my feet, I was transferred to the prison “hospital.” When I regained consciousness, another prisoner told me that my name had been called by authorities several times. “Who was looking for me?” I wondered. I didn’t immediately understand what was going on, but when I returned to my cell and saw 60 other prisoners standing in the halls, I began to piece it together.

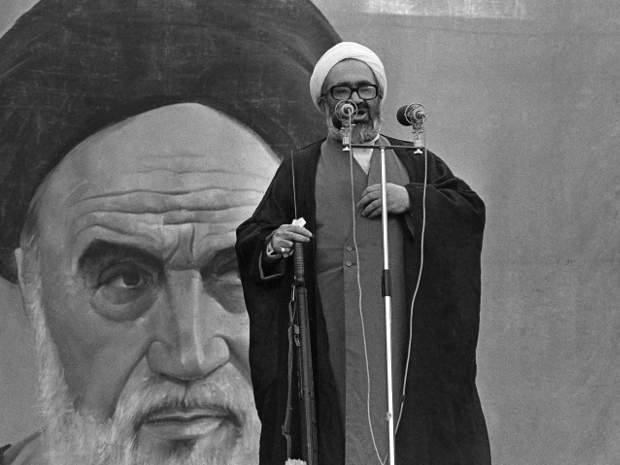

Soon afterward, I learned that Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini had issued a fatwa ordering the massacre of political prisoners, particularly supporters of the MEK. All the occupants of the 60 cells had been executed. No one was spared — no one.

And they were far from the only ones. Khomeini had dispatched amnesty committees to the prisons, which is a fancy term for a death squad. They asked each political prisoner about his or her allegiances and anyone who failed to repent their former political activities and fully submit to the theocracy was charged with “waging war on God.” This vague charge remains on the books and is often used to execute those with whom the regime disagrees.

In 1988, it was used an as excuse to turn Iran’s prisons into slaughterhouses. Prisoners were rounded up and hanged, six at a time. The bodies were transferred to mass graves in meat trucks at night. Prison authorities operated with such ruthless efficiency that on some nights, up to 400 were executed.

In total, about 30,000 prisoners were massacred in a matter of a few months. But because I had been hospitalized, unbeknownst to some of the guards, my name was passed over by the executioners and I became one of about 250 political prisoners who survived the death squad in Evin.

When I was released in 1991, I worked hard to determine the real scope of the 1988 massacre. Ever since I escaped the country a few months later, I have been trying to help bring the massacre to the world’s attention.

Make no mistake: the international community has known about this crime for quite some time. Over the years, human rights organizations, including Amnesty International, have called it a crime against humanity. According to Geoffrey Robertson, the former judge at the UN Special Court for Sierra Leone, the 1988 bloodbath was the largest mass execution of prisoners since the Second World War. Yet there has never been any international inquiry into the incident, and the masterminds and perpetrators of this heinous crime have gone unpunished.

But the Aug. 9 revelation of an audio recording of the former heir-apparent to Ayatollah Khomeini has provided a new source of hope for those who aspire to shed light on this incident. In the 1988 recording, Ayatollah Hossein-Ali Montazeri chastises members of Tehran’s Amnesty Committee for their participation in what he calls the greatest crime of the Islamic Republic. He details some of the most shocking aspects of the massacre, including executions of pregnant women and teenage girls, and the targeting of people whose support for the MEK extended no further than reading its newspapers and magazines.

Although Montazeri was cast out of the regime as a result of his dissent, he was a prominent figure in 1988. The regime cannot disregard his recorded words and this fact has led to renewed public discussions of the massacre. That conversation now threatens to spread across the globe and bring newfound scrutiny to this dark chapter in modern Iranian history.

What makes it more relevant is that dozens of the top perpetrators of the massacre are currently holding key positions in the regime, including Mostafa Pourmohammadi, justice minister in the Hassan Rouhani administration, who publicly gloated on Aug. 28 about his role in the massacre. And it is these very same people who continue to persecute Iranian dissidents today, making the clerical regime the world leader in the number of executions per capita.

Very much to its credit, Canada has been a leading voice on human rights in Iran for the past decade. It is time for the international community, including Canada, to finally move to prosecute the perpetrators of this massacre. A UN inquiry and fact-finding task force is the first step — one that is long overdue.

Mostafa Naderi is a former Iranian political prisoner who spent 11 years in an Iranian prison and is one of the few survivors of Iran’s 1988 massacre of political prisoners.

National Post

http://news.nationalpost.com/full-comment/mostafa-naderi-no-one-was-spared-a-former-iranian-political-prisoner-on-the-1988-massacre-he-narrowly-escaped